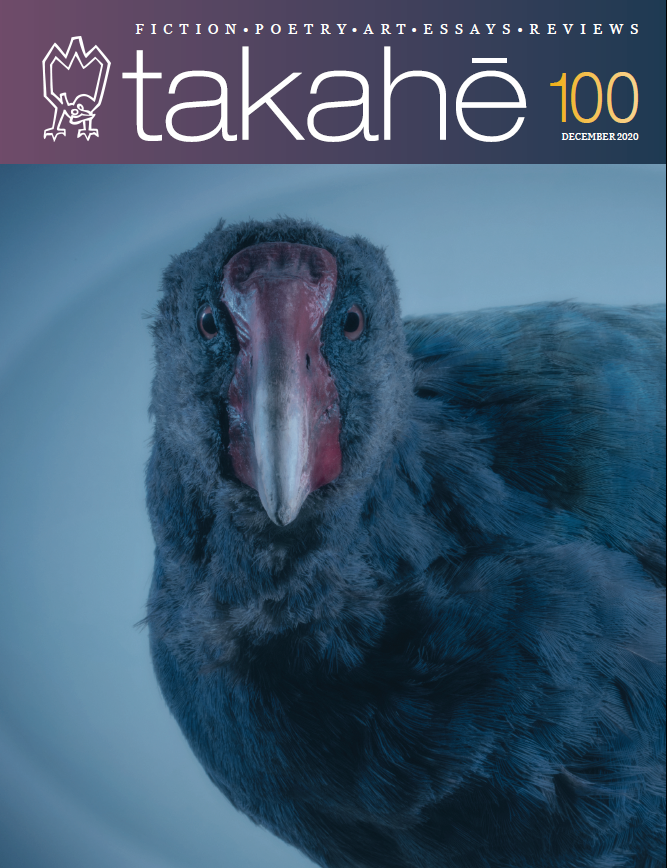

This essay first appeared in takahē 100, released in December 2020:

When we come across something beautiful, do we look at the object to examine its beauty or look around us to see who else likes it and why? Is our demand for agreement but our lack of consensus about beauty threatening the survival of art? And why does it feel like we have seen this before?

On a cool summer evening I attend a house concert in Mangere Bridge; Mozart performed for violin and piano, Beethoven for cello and piano, the audience crammed on chairs and on the floor around the edges of a baby grand.

“His sister is famous, I follow her on instagram,” my friend whispers from a beanbag on the floor. She’s speaking of the cellist’s sister.

The pianist (in whose converted garage we have all convened) tells us we will probably recognise the Schubert, it’s been used in the soundtrack for at least nine movies or TV shows.

Franz Schubert’s movement ‘Andante con moto’ from Piano Trio No. 2 in Eb, Op. 100 does sound familiar. Perhaps. Maybe I’ve heard it on a TV ad for a bank. There used to be one I’m sure, with a horse and a beach and swelling music. But maybe that was a different piece. At home I look up what TV and movies it has been used on. I find fourteen on Wikipedia:

- Miss Julie, a 2014 period drama film

- Barry Lyndon, a 1975 period drama film

- The Hunger, a 1983 erotic horror film

- Crimson Tide, a 1995 movie thriller

- The Piano Teacher, a 2001 French erotic psychological thriller film

- L’Humme de sa vie, a 2006 French film

- Land of the Blind, a 2006 political satire movie

- Dear White People, a 2014 comedy-drama movie

- Recollections of the Yellow House, a 1989 Portuguese film

- The Way He Looks, a 2014 Brazilian romantic drama movie

- John Adams, a 2008 period drama miniseries

- The Mechanic, a 2011 action thriller miniseries

- The Killing Season, a 2015 political documentary series where Piano Trio No. 2 (Schubert) was the opening piece

- American Crime Story, an ongoing true crime TV show

I think I’ve seen Crimson Tide.

A few days after the concert we go camping north of Auckland. Sitting on the beach I watch three brothers playing. One, exhausted and cold, wraps himself in a towel and drops down to the sand. His brother sits on his head and farts in his face. The boys’ parents laugh while they splash about on their stomachs in the sea.

Why are we entertained by what entertains us; artful or fartful? And why does what entertains us so often divide us? It is no longer easy to tell. High art or low – it’s been replaced by an unspooling thread the ends of which no one can find. There is no Kantian aesthetic consensus in our age, hardly any consensus at all, we are instead face down in aesthetic huddles. In New Zealand, like much of the west, art and entertainment, even culture, live “almost entirely under the rubric of consumption,” according to A.O. Scott. And as we gobble we no longer know whether we are tasting something we like or have simply ordered something to our tastes.

Unspooling thread: Franz Schubert’s movement ‘Andante con moto’ from Piano Trio No. 2 in Eb, Op. 100 was written in 1827. In 2014 it was in the soundtrack of Miss Julie. Miss Julie stars Colin Farrell who was the villain Bullseye in the 2003 film Daredevil. Ben Affleck was the titular hero, Matt Murdock, and was once engaged to Jennifer Lopez. The pair made regular appearances in tabloids which nicknamed them ‘Bennifer’. For her part, Jennifer Lopez starred in Maid in Manhattan with Ralph Fiennes who was nominated for an Academy Award for portraying a Nazi war criminal in Schindler’s List. Featured among the score in Schindler’s List was Bach’s English Suite No. 2.

Better Living Through Criticism is a 2016 collection of essays about criticism, art, entertainment and taste by A.O. Scott (unspooling thread: an advertisement for plastic bags in New Zealand shrilling – better living everyone!). Scott argues that art which survives the ages, art like the music of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, has passed through a process of being judged and found valuable. “We found ourselves able to make things, and also to judge them,” he says.

And there is truth to this when a piece of music two hundred years old appears in different media, however obscure, made around the world in America, Britain, France, Brazil, Australia and Portugal. Yet I can’t help but believe that fart jokes have also survived the ages. Surviving not because they have been judged and found valuable but because they move people to mirth. Their value not in being artful but being entertaining.

Scott, in his way, agrees, saying that a nonprofessional, unspecialized, agendaless audience often cares only whether entertainment moves them and by this alone it becomes, to the masses, art. And so art must entertain and entertainment need not have any other value. What entertains us becomes what makes us laugh, cry or feel anger. But what you laugh at I feel angry about. What creates in me tears created in you boredom. And as Scott says, there is nothing more personal than feeling something. So we are divided and reform into groups which are consensual about what moves us. And about what does not.

Western Culture has formed huddles before, showing to each other only our backs. We were once moved by God and so divided ourselves by what god we believed in, such as when the English expelled all Jewish people from the island in the 1200’s. Then it was which version of that god you believed in which divided – German theologian, pastor and reformer Martin Luther led one movement away from the Catholic church retaining a belief that “Christ’s flesh and blood are physically present in the bread and the wine,” says Michael Massing in his 2018 book Fatal Discord. To French theologian, pastor and reformer John Calvin this was diabolical. Massing paints a picture of the medieval reformation where the number of huddles grew and grew, reconciliation vanished and the whole movement was weakened while Christian killed Christian in the name of heresy. It seems madness now; it seemed madness then. “To kill a man is not to defend a doctrine, but to kill a man,” said a contemporary French preacher, theologian and humanist, Sebastian Castellio. To say so simple a statement carried such risk he would not attach his name to the printed comment. Still, it caused the expected outrage – Calvin hunted for the author’s name and, according to Massing, for years he “led a campaign to silence and defame [Castellio].” Is any of this sounding familiar?

Unspooling thread: Philip Larkin wrote (on an entirely different subject) when we look at another and at all that moves them –

“It becomes still more difficult to find

Words at once true and kind

Or not untrue and not unkind.”

Somehow, so much of what we can’t work out in our world today comes down to this – the problem of huddles growing and growing, reconciliation vanishing and hateful words being thrown. Art is not immune. The whole movement of the creative arts is being weakened by the removal of beauty and value and by becoming only entertainment which must move the viewer or be discarded. What we thought was opening art up – art can be anything! – instead has made the arts seem even more exclusive and excluding, even pointless to a general audience who feel nothing and see no beauty in it. The irrevocable undoing of consensus – aesthetic consensus as Scott would have it – is a problem we cannot ignore.

Scott explains how eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant decided to face this problem by creating a hierarchy of aesthetic judgement. Imagine it like those healthy eating pyramids we grew up with – at the bottom is the agreeable, the middle is taken up by the beautiful and the tiny triangle at the top is reserved for the good. For the top and middle of the pyramid there is only subjective universality – what is beautiful to one is beautiful to all. Of course we can’t prove it, we must accept it is subjective while also standing by our claim to universality. Said Kant, “the judgement of taste is not an intellectual judgement and so not logical, but is aesthetic – which means that it is one whose determining ground cannot be other than subjective.” Or as Scott says, “there is, axiomatically, no disputing taste, and also no accounting for it…there is no argument, but then again there is only argument.” A stand like that requires humility to stop a descent into fistfights and name calling. A certain level of accepting the unexplainable.

Leave that to sink in for a moment and look at the bottom of the pyramid; the agreeable. For the vast amount of things if something is agreeable we should, says Kant, indicate and believe that it is agreeable only to us individually – “fart jokes are so agreeable to me.” We don’t need to demand that others agree with us and we can’t really. We gain pleasure in it because it satisfies a sense or we find it useful or moving. It is, says Donald Crawford in The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, agreeable to us because we have an interest in the existence of the object. Here we find things which give us a “purely individual state of pleasure,” says Scott. It’s great if we find others who agree with us but these things shouldn’t divide us because we don’t need to demand the same viewpoint from others.

This bottom of the pyramid should contain most things.

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (known as Erasmus) was a Christian scholar at the time of the reformation. He was horrified by all the small theological differences which seemed to be dividing the movement. Why do we all need to agree on some of these side issues? he asked. Let each man decide whether to confess or not; whether to abstain on fast days or to eat. Do not at each religious statement shout “Heresy, heresy! To the fire, to the fire!” when it is not a doctrine which matters. Michael Massing in Fatal Discord says that it was because of statements such as this that all sides hated Erasmus – the Catholic church banned his work and Martin Luther spat back that on matters of doctrine there could be no compromise. For a publication called On Mending the Peace of the Church Luther accused Erasmus of being “an evil enemy sowing tares among the wheat.”

Why then, why now, can’t we follow Erasmus and Kant? Scott argues that the undoing of a consensus on what is beautiful, what is good, has caused Kant’s firm pyramid to unspool. When we come across something beautiful we no longer look at the object to examine its beauty but we look around us to see who else likes it and why. The crowd around us has become more important than the beauty around us. We have made everything agreeable and then frantically looked around insisting on finding people who agree with us. This is not consensus.

Unspooling thread: Thierry de Duve wrote a book in 1996 called Kant after Duchamp where he invites readers to imagine they are an extraterrestrial. Duchamp’s most famous and enduring work of art, Fountain, is a urinal. ‘Readymade’ is the term he coined for it, taking a manufactured object and by the choosing and labelling acts of the artist removing its reademade purpose and creating readymade art. Just as to some a fart is a readymade joke.

For most things we don’t need to agree. Can’t we acknowledge that? And can’t we also acknowledge as Scott says that some works of art still “survive the circumstances of their making and find adherents in radically divergent times and places”? In Kant after Duchamp, de Duve says that “an essence called art maintains itself unchanged throughout its succession of avatars.” On these things we should come out of our huddles and turn our gaze on them in contemplation. We should use discussion and criticism and silence to see where the subjective universality might still exist. It will be difficult to attempt but might not be as injurious as we think if we retain our humanity. J.H. Bernard translated Kant’s thoughts on this to be, “we are justified in presupposing universally in every [person] those subjective conditions of the judgement which we find in ourselves.”

“None are flawless, all

are fated to fall. There is

an immense brotherhood

that one wishes to belong to,

in spite of oneself, deep down.”

- Unspooling thread by Brian Turner.

A call for refinding where we can have consensus is not a demand for uniformity; it’s not a weakness and we need to stop thinking it is presumptuous or coercive. Consensus, says de Duve, has another name: peace-on-earth. He says, “consensus, when it exists, is always suspect of not having been spontaneous…but when it does not exist it needs to.” When consensus is broken in art we call it avant-garde. But there must be consensus to begin with for the avant-garde to be meaningful and not simply chaos.

Our children have a six-metre long sprinkler. We set it up one hot summer day on our Auckland lawn. It has the head of a snake, the hose attaching like a long extended tongue. Its sunshine green body is dotted with holes which shoot out water.

“The snake is peeing! Look at all the snake pee!” our children screech.

“I’m turning on some classical music for them at lunchtime,” my husband says.

“To make them less vugar?” I ask.

“Exactly.”

Works Uses:

Better Living Through Criticism by A.O. Scott, published by Penguin Press (U.S.A) in 2016

Don’t Trust, Verify in Wired-27.03, article by Zeynep Tufekci published by Conde Nast (U.S.A) in 2019

Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther and the Fight for the Western Mind by Michael Massing, published by HarperCollins (U.S.A) in 2018

In a Sponsor’s Tent, poem found in Selected Poems by Brian Turner, published by Victoria University Press (New Zealand) in 2019

Kant after Duchamp by Thierry de Duve, published by The MIT Press (U.S.A) in 1996

The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, third edition edited by Berys Gaut and Dominic McIver Lopes, published by Routledge (Great Britain) in 2013